Vol No: 5 Issue No: 2 eISSN:

Dear Authors,

We invite you to watch this comprehensive video guide on the process of submitting your article online. This video will provide you with step-by-step instructions to ensure a smooth and successful submission.

Thank you for your attention and cooperation.

1Ms. Tejashwini Huchannavar, Department of Pathology, Padmashree Institute of Medical Laboratory Technology, Bengaluru, Karnataka, India.

2Department of Pathology, Padmashree Institute of Medical Laboratory Technology, Bengaluru, Karnataka, India.

3Department of Pathology, Padmashree Institute of Medical Laboratory Technology, Bengaluru, Karnataka, India

4Principal, Padmashree Institute of Medical Laboratory Technology, Bengaluru, Karnataka, India

*Corresponding Author:

Ms. Tejashwini Huchannavar, Department of Pathology, Padmashree Institute of Medical Laboratory Technology, Bengaluru, Karnataka, India., Email: tejukh77@gmail.com

Abstract

Background: Increased stress levels, when chronic in nature, may lead to diseases like hypertension, cancer, early ageing and fertility issues along with menstrual irregularities in females and lower sperm count in males as the age increases, due to hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis dysregulation.

Aim: The aim of the present study was to assess the effect of perceived chronic stress and body mass index (BMI) in a subset of healthy population of male volunteers aged 18 to 45 years and female volunteers aged 18 to 40 years.

Methods: The selected male and female population were stratified into age and stress matched groups and one time dehydroepiandrosterone-sulfate (DHEA-S) levels were ascertained to evaluate any changes DHEA-S levels were measured using Chemiluminescence method within six hours of collection of the blood samples, randomly collected at different time points in the day, and were then statistically evaluated using Mini Tab statistical tool.

Results: The lower levels of DHEA-S were more pronounced in males than in females in age and stress matched stratified groups. With increasing age, the fall in DHEA-S was seen in both the genders, but a significant fall in DHEA-S levels was noted after the age of 35 years in males than in age matched females, even when BMI was considered as a new variable in the study.

Conclusion: This study does not demonstrate any significant correlation between DHEA-S levels and increasing levels of perceived chronic stress and BMI in both the genders. The DHEA-S levels showed a decline with age as is a normal trend.

Keywords

Downloads

-

1FullTextPDF

Article

Introduction

Stress can be acute or chronic, and may have physical, emotional and psychological impact on the human body. The human body responds to stress by releasing hormones like cortisol, adrenaline and noradrenaline, depending on the stress levels and the situation encountered. The “Fight and Flight” response encount- ered during acute stress situations is an immediate response. In addition, other hormones such as dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA), dehydroepiandro- sterone-sulfate (DHEA-S) and cortisol are released during chronic stress due to chronic activation and dysregulation of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis as continuous release of these hormones leads to generalized stressed environment, impacting the homeostasis of the normal body.

The stress hormones of the adrenal gland such as cortisol, adrenaline and noradrenaline are constantly increased due to the continuous stimulation of Zona fasciculata by adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH).1,2 During chronic stress, this can cause deleterious effects on the body with the production of oxidants and free radicals in the body leading to cardiovascular diseases, atherosclerosis, anxiety, premature aging, cancer, chronic diseases and neuromodulation.1-6

The other hormones released by the adrenal gland from Zona reticularis, such as DHEA, DHEA-S are in smaller amounts when compared to those released from ovaries, testis, brain tissue.1,2

The interconversion between DHEA and DHEA-S hormones at cellular level is an important phenomenon where the hormones are converted in the fat tissue.7 They are converted into androgens in males and estrogens and androgens in females in the fat tissue.1,2

There are conflicting reports from different scientists on the levels of DHEA and DHEA-S in acute and chronic stress. Various studies have reported higher values of DHEA in acute stress and lower values of DHEA-S in chronic stress, while some studies have not found any link in the levels of DHEA or DHEA-S in either acute or chronic stress.8-12

The aim of the present study was to determine whether the DHEA-S levels vary with chronic stress and Body mass index (BMI), in age and stress matched controls among randomly selected healthy male and female volunteers visiting for health check-ups.

Materials and Methods

Volunteers from Padmashree Diagnostic Centre, Bangalore, India visiting for general health checkup were selected randomly and a prospective cohort study group was set up with 500 volunteers consisting of 250 males and 250 females to determine the correlative effect of perceived chronic stress levels and DHEA-S levels. BMI was estimated in selected individuals of the total sample (Female- 75 and Male- 87, a total of 162 had their BMI estimated).

Age and stress matched stratification was done and various groups were inbuilt in the study among the selected males and females.

Consent for participation was obtained from the volunteers after providing details about the objectives of the study. Answering of DASS-21 (Depression Anxiety Stress Scale-21) questionnaire to assess the stress levels was a mandatory requirement for enroll- ment of the volunteers before the collection of blood samples. The DASS-21 comprised of 21 questions and were scored from 0-4. The study volunteers provided responses for 21 questions and a total score was calculated, then categorization of stress levels as ‘Normal’, ‘Mild’, ‘Moderate’, ‘Severe’ and ‘Very severe’ (for simplifying the process we had clubbed severe and very severe into a single category as “severe”) was done accordingly. In a selected sample, measurement of height and weight was undertaken for the BMI estimation.13 The samples were randomly collected during the day (previous day fasting was not made mandatory criteria for enrollment) and were processed within six hours of collection; simultaneously DHEA-S values were determined. Analysis was done by Chemiluminescence method. The stress levels were categorized into normal, mild, moderate and severe. No other parameters such as smoking, menstrual cycle phase and physical exercises were considered in this study.

The Mini Tab statistical tool was used for statistical evaluation to correlate DHEA-S levels, stress levels and BMI in male and female population, in age and stress matched groups.

Results

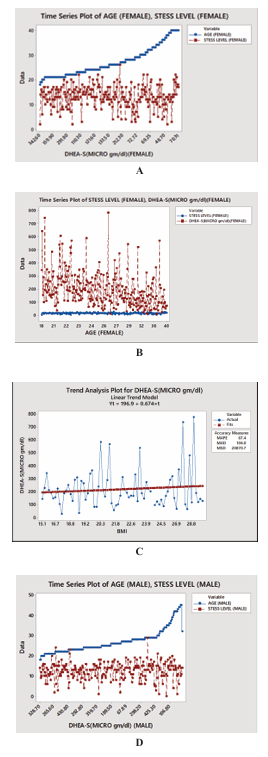

The statistical results are depicted below in the form of DHEA-S levels against the stress levels in females in Figure 1A and also the DHEA-S levels against the age groups in Figure 1B. Figure 1C represents the BMI and DHEA-S levels among females.

The statistical results are depicted below in the form of DHEA-S levels against the stress levels in males in Figure 1D and also the DHEA-S levels against the age groups in Figure 1E. Figure 1F represents the BMI and DHEA-S levels among males.

There was no correlation between stress and BMI in both male and female groups when compared to DHEA-S levels.

Table 1 depicts the variables such as age and BMI along with DHEA-S levels and stress levels in male and female groups.

A total of 87 males were included with a mean age of 25.6±4 years, whereas the female group consisted of 75 subjects with a mean age of 25.3±5 years. The mean BMI of male and female subjects was 23.9±3.7 and 22.5±4.2, respectively.

The mean DHEA-S levels in male and female subjects were 292.7±156.6 and 221.4±145.4, respectively.

The stress levels recorded in male and female subjects using DASS-21 questionnaire were 11.9±3.7 and 12.8±4.4, respectively

DHEA-S and stress levels did not show any correlation in both the age matched groups.

Discussion

The correlation between DHEA-S levels and stress levels reported in various studies are contradictory. Few studies documented lower values of DHEA-S in stressed individuals while a few reported higher values. Certain studies did not find any correlation between DHEA-S and chronic stress levels. The present study was carried out considering only two parameters, stress levels and DHEA-S levels in age and stress matched male and female individuals and BMI, without considering any other parameters. The plausible variations observed in various studies could be due to inbuilt hormone homeostasis in the body with an inherent property to maintain an optimal level of hormone balance for normal functioning of the body with minimal fluctuations.

It was decided to test this hypothesis with consideration of correlation of stress levels and BMI with DHEA-S levels, without considering the phases of menstrual cycle, smoking status and physical exercises in female population. Similarly, among males, smoking status and physical exercises were not considered. DHEA-S one time values were analyzed to understand the intricacies involved in measuring just the DHEA-S levels and its correlation with chronic stress levels and BMI.

Du et al. analyzed the stress associated with work stressor levels and plasma DHEA-S among sixty-three bus drivers. The DHEA-S level was higher in drivers of younger age as well as drivers with more concerns regarding their salaries and bonuses. None of the drivers showed association between any stressor or satisfaction and urine cortisol & blood DHEA-S levels.14

In our study, no correlation between DHEA- S levels and stress was found, probably because though the stress levels have been graded, we could not estimate the period of stress among individuals who participated in the study. This was a drawback in the current study as prolonged stress may shift the balance towards cortisol production and lowering the production of DHEA- S levels.

Gadinger et al. in his demand-control-support (DCS) model studied 596 employees with administration and non-administration responsibilities. Twenty-four-hour urine cortisol levels, fasting morning plasma, DHEA-S estimation showed that administrative employees with high work request had low cortisol to DHEA-S ratio with higher levels of DHEA-S, whereas non-administrative employees had no affiliation to cortisol to DHEA-S ratio and request at work. In our study, we could not have such categorization as only two groups were considered, stressed and not-stressed (general stress levels). In addition, we did not measure the cortisol levels in the urine which is an important aspect of stressor response.15

Jeckel et al. compared salivary DHEA-S levels in age matched female guardians (stressed group) and non guardians (non-stressed group) and found lower levels of DHEA-S in guardians as compared to non-guardians by 32%. This study had both the amount of stress and period of stress measured. The limitation of our study was that the amount of stressed was measured but not the period of stress.16

In all the studies quoted here, BMI was one of the anthropometric measurement that was a part of data collection and no correlation with DHEA-S values was done with BMI as an individual variable.

The dynamic status of the hormone levels and their f luctuations, which is a normal phenomenon, should be considered before interpreting the results. The one-time peripheral blood sample measurement of DHEA-S levels in our opinion may not be sufficient to find a correlation, as these hormones are in dynamic state and vary as per the physiological status more often to keep the body in homeostatic state. The inter convertibility of these hormones makes it more difficult to understand and correlate its levels when in dynamic state.7 Chronic stress which is again inter observer dependent and subject to individual perception is another highly variable parameter. When these two highly variable parameters are corelated, it becomes more difficult to find a link between these two parameters. This could be the probable reason why different authors have different conclusions regarding the DHEA-S values and chronic stress. It is of paramount importance to collect the right sample at a destined point in the day, preferably early morning fasting blood sample and select an ideal method like radioimmunoassay (RIA) or high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) for proper estimation and better correlation.

In the current study, no significant correlation was found between DHEA-S levels and increasing levels of perceived chronic stress and age. In few studies, lower levels of DHEA-S in females with chronic stress was observed.

The main shortcoming of the present study was that the BMI, smoking status, menstrual phase, physical exercises in females, and BMI, smoking status and physical exercises in males were not considered while enrolling the volunteers. This may have skewed up the f inal findings. But it gives us an insight of the variability that exists in measuring the two highly variable entities against a homeostatic environment which the body intricately balances.

Conclusion

We would like to conclude with a positive note that further studies which are appropriately designed are required to evaluate the correlation taking into account the inter human variability, ethnic differences, inherent genetic variability, human body’s ability to maintain homeostatic environment, while measuring the hormones which are in dynamic state. The method of estimation also plays an important role in determining the exact values for a proper correlation.

Conflict of Interest

None

Funding

This study was supported by a grant from the Rajiv Gandhi University of Health Sciences, Bangalore, India. The funder had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Ethics approval: The ethics committee was an independent body from NU Hospitals Ethics Committee, Bangalore, India

Supporting File

References

- Theorell T. Fighting for and losing or gaining control in life. Acta Physiol Scand 1997; (Suppl 640):107-111.

- Henderson M, Glozier N, Holland Elliott K. Long term sickness absence. BMJ 2005;330:802-803.

- Kivimaki M, Nyberg ST, Batty GD, et al. Job strain as a risk factor for coronary heart disease: a collaborative meta-analysis of individual participant data. Lancet 2012;380(9852):1491-7.

- Epel ES, Blackburn EH, Lin J, et al. Accelerated telomere shortening in response to life stress. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2004;101:17312-17315.

- Wolkowitz OM, Epel ES, Reus VI, et al. Depression gets old fast: do stress and depression accelerate cell aging? Depress Anxiety 2010;27:327-338.

- Labrie F, Luu-The V, Labrie C, et al. DHEA and its transformation into androgens and estrogens in peripheral target tissues: intracrinology. Front Neuroendocrinol 2001;22:185-212.

- Geetharani B. Impact of psychological stress at work is related to lower levels of DHEA and DHEA-S levels. Int J Stat Syst 2017;12(1):1-13.

- Goodyer IM, Herbert J, Altham PM, et al. Adrenal secretion during major depression in 8-to 16-year olds, I. Altered diurnal rhythms in salivary cortisol and dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) at presentation. Psychol Med 1996;26:245-256.

- Kroboth PD, Salek FS, Pittenger AL, et al. DHEA and DHEA-S: a review. J Clin Pharmacol 1999;39:327-348.

- Schell E, Theorell T, Hasson D, et al. Stress biomarkers’ associations to pain in the neck, shoulder and back in healthy media workers: 12- month prospective follow-up. Eur Spine J 2008;17:393-405.

- Ohlsson C, Labrie F, Barrett-Connor E, et al. Low serum levels of dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate predict all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in elderly Swedish men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2010;95:4406-4414.

- Rotter JI, Wong FL, Lifrak ET, et al. A genetic component to the variation of dehydroepiandro- sterone sulfate. Metabolism 1985;34:731-736.

- Lovibond SH, Lovibond PF. Manual for the depression anxiety and stress scales (DASS21) Second edition. Sydney, NSW: Psychology Foundation of Australia; 1995. p. 1-3.

- Du CL, Lin MC, Lu L, et al. Correlation of occupational stress index with 24-hour urine cortisol and serum DHEA sulfate among city bus drivers: A cross-sectional study. Saf Health Work 2011;2(2):169-75.

- Gadinger MC, Loerbroks A, Schneider S, et al. Associations between job strain and the cortisol/DHEA-S ratio among management and nonmanagement personnel. Psychosom Med 2011;73:44-52.

- Lac G, Dutheil F, Brousse G, et al. Saliva DHEAS changes in patients suffering from psychopathological disorders arising from bullying at work. Brain Cogn 2012;80:277-281.